Ailsa Craig

Nesting in colonies of tens of thousands of pairs, the rocky cliffs and islands around the UK hold over half of the world’s population of Northern Gannet (Morus bassanus), with the world’s largest colony being Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth (75,000 pairs) and the colony on Saint Kilda (60,000 pairs).

Traditionally these huge colonies are counted by aerial photography, and only really need a detailed count about once a decade. With these birds being impacted extremely badly by HPAI in 2022 and 2023, new counts are now being undertaken by drone, which is a lot easier (in theory) and cheaper than paying for dedicated photography from an aircraft. I’ve never carried out drone photography of cliff nesters so was asked if I’d like to help out with the count at Ailsa Craig, a lump of volcanic rock 16km (10 miles) off the coast of Ayrshire in South West Scotland.

(Note - I was too busy paying attention to the drone flying to actually take many pictures of birds, so this post is really about the scenery)

|

|---|

| Viewed from Girvan, looking out across the beach to the dome-shape of Ailsa Craig on the horizon. |

Ailsa Craig is famed for being the source of the finest granite for making Curling Stones. A local company holds the sole licence to quarry here, and takes granite off the island about once a decade, most recently just this winter and youtuber Ruth Aisling made a fantastically informative video about the whole process so you can watch that rather than me try to explain.

|

|---|

| Rocky Ailsa Craig in the sun, cliffs white with seabirds with patches of green vegetation. Gannets swirl in the blue sky above. |

The boat trip is about an hour out of Girvan, and includes a circuit of the island so we could see the dramatic cliffs rising out of the water, covered in nesting seabirds - Gannets are the most obvious, but colonies of guillemots, razorbills, kittiwakes, fulmar, and, on some of the steep grassy slopes, puffins ambling about between their burrows. Tysties (black guillemots) were on the water, although I couldn’t spot any on the cliffs.

|

|---|

| A closer view of Ailsa Craig in the sun, cliffs white with seabirds tower about 200m over the sea, capped with a grassy dome. |

Dozens of Manx shearwaters flew past the boat as well, presumably these nest on the island now, especially after rats were eradicated in the early 90s, but breeding has yet to be proven. You can read about the first succesful rat eradication in the UK in this 2001 article by Bernie Zofrillo, who led the eradication project in the 1990s.

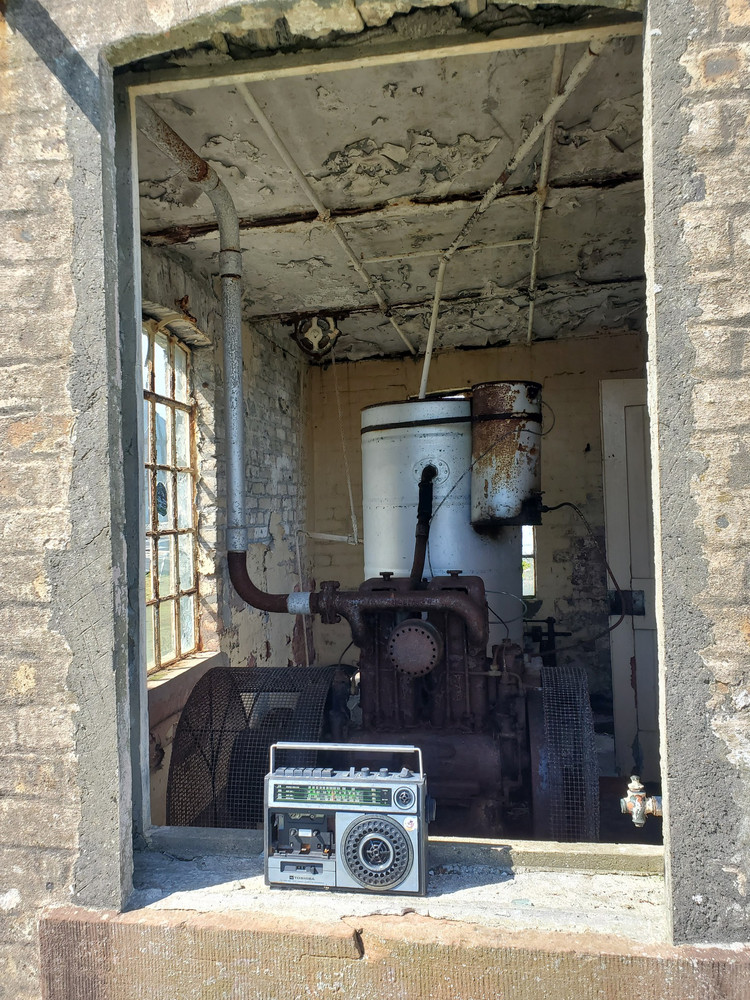

Once on the island, we pitched our tents by the old gas works. This was where coal gas was generated to power the lighthouse and foghorns until 1911, when the lamp was switched to parafin. The flat part of the island is covered in remains from both the lighthouse and quarrying infrastructure, with a 3-foot gauge rail for the lighthouse still in place, and plenty of tracks and evidence of quarrying. The lighthouse is still operational, and being painted by three workmen when we were on the island.

In the afternoon sunshine, we walked from the lighthouse clockwise along the track left by this winter’s rock extraction, we passed the south foghorn, on top of a concrete dome and with compressed air cannisters rusting alongside. Huge boulders litter the shore line, we walked as far as “Trammins” and flew the drone to take photographs of the gannets nesting on the 200m high cliffs towering above.

After a succesful flight, we returned for a peaceful evening of birding and an early night. I slept very well in my tent, and we were up at 6 but had to wait for the low cloud to shift and the tide to go out a little before walking anti-clockwise this time, following a trackway that carried the piped gas to power the north foghorn. In places it bridged inlets, these were rusted away so we dropped to the beach then climbed back up the other side.

|

|---|

| A narrow concrete walkway crosses the rocky beach. Where there are narrow inlets in the steep rock, it is bridged with rotten wooden and partiually missing slats across rusted metal framework. |

We also stopped at the remains of the old North Quarry, and puzzled a bit at vast piles of stone with cylinders cut out, and the stone cylinders themselves, before it clicked that these were where they used to cut out the basic curling stone shape before shipping them off the island, presumably easier to do so and ship off here before larger boats and trucks made taking whole boulders off the easiest method.

Tempted to take a “raw” curling stone back with us but a little heavy for our backpacks, we walked on, past the northern foghorn.

We passed a dry seacave, and had a look inside - nothign but bones of seals and rabbits, but then we spotted a few pieces of graffiti, from 1923 and 1886.

Our walk took us close to a very low colony of Auks (no pics - we were concentrating on getting past them as quickly as possible to minimise disturbance). This colony could not have existed when rats were on the island. Elsewhere steep cliffs protect these birds from losing their eggs and chicks to predation, but here on the ground there’s no defence. Wonderful to see, therefore, a growth in the colony thanks to the lack of danger.

Soon we were underneath the main Gannetry on the vast cliffs, and carried out the drone survey. The south-west point of Ailsa Craig holds a deep seacave that makes walking a loop of the island impossible, so once complete we walked back the way we came, passing a simple wooden structure that looked like a very old watcher’s hide?

We returned and found we still had a good few hours before the boat. I climbed the incredibly steep and loose path through thick bracken, reaching the castle, a stone 16th century tower. Just above it, as I carried on up the slope, was a tanked spring, one of four on the island. (the main source of water for our trip was me knocking at the lighthouse and asking if we could have a bottle of water when we realised we hadn’t brought enough)

Through the bracken, I could follow the path a little further, but then lost it in the bracken on the rocky slope. I didn’t feel like going any further, so went back to the castle for a sandwich and a chat with a kayaker who had just arrived.

After returning down the hill, I explored the buildings more, and chatted with daytrippers (birders) who’d been dropped off. The old Quarry Master’s Cottage was used by the local ringing group until the roof collapsed, which is a real shame, but I imagine the costs of maintaining and repairing buildings out here is pretty significant.

What a great trip out! I feel very lucky to have been allowed to camp on the island and have the time to explore it fully. You can get a trip out from the port of Girvan in Ayrshire, it’s about an hour to the island, you get 2 hours ashore, and then a trip around the island and back again. Very much worthwhile. And they might let you cuddle a lobster on the boat back.

|

|---|

| Me, grinning, on a boat, holding a large blue lobster. Two older women stand behind me. |